Pursuing Data Ownership in the Age of Surveillance Capitalism

Data is valuable, the modern world is built on it. It's time to rethink our relationship with the data we produce.

Data collection is here to stay, and that's not inherently bad, as it has great potential to power good things like smart cities, personalized health, and even recommendation algorithms. After all, we all like when Spotify hits us with a masterfully curated banger.

But in reality, everything that can possibly be made into a data point, from keystrokes, clicks and browsing history, to your GPS location and even health data, will be. It's all harvested in bulk, because there's a market for it. Your data is a valuable commodity that can be bought, sold, and ultimately used to predict and influence human behaviour. The product of all that data processing are powerful algorithms, capable of things like price discrimination1, radicalization2 and political manipulation3.

While we generate tons of data through our daily lives, we don't often think about where it goes, who profits from it, or how it's used. Things like terms and conditions, and cookie banners do give us the illusion of control, but in practice, they function more as legal shields for companies than meaningful tools for users. Most users blindly accept these terms without truly understanding the extent of the surveillance they're consenting to. Even people who do care about their privacy often choose to accept these terms for the sake of convenience or the lack of better options. I mean, if one needs MS Word for work, it's hard to justify spending over an hour reading their terms, since the options are just accepting or not using the product at all.

For example, as much as I dislike Meta's business practices, it's virtually impossible to live without WhatsApp in Brazil (and most of the world, for that matter), as it is the main (and sometimes sole) communication tool of over 93% of the population in the country. The oligopolistic grip of Big Tech over our digital infrastructure makes them pretty much unavoidable.

But why should we strive to avoid them?

We've already seen what happens when we cede too much for the sake of convenience: Email, a decentralized open protocol that would allow anyone to host their own mail server, is now effectively controlled by major companies like Google and Microsoft. Their gatekeeping raises the barrier of entry and makes avoiding their services not impossible, but very impractical. For example, you usually can't run an email server from your home network, because those residential IP ranges tend to be blacklisted by the big players. You have to rent a server from some company, but then many of those (like DigitalOcean) will not even allow you to open SMTP ports, making it impossible to use them as mail servers.

Even if you can find a provider that allows you to open SMTP ports, hosting your own mail server today means having to deal with your email being constantly flagged as spam by the big players. Possibly wasting hours trying to get your IP out of a blocklist you have no idea how you've gotten into in the first place. This isn't really due to anything technical. A set of perfectly configured SPF/DKIM/DMARC records and a good mail server will likely still have you talking to Microsoft Support, trying to figure out why on earth Outlook isn't accepting your emails... This guide goes a lot deeper on the challenges and technical details of self-hosting an email server, if you're crazy brave enough to try it.

I'm not saying everyone should host their own email, that's obviously a terrible idea. As DigitalOcean themselves pointed out, email servers are complex and require a lot of knowledge to set up and maintain, but, as we all remember every time Cloudflare goes down, the health of the internet depends on decentralization. We shouldn't let a handful of billion-dollar corporations control what are effectively essential services. Convenience shouldn't come at the cost of privacy or control. Supporting open standards, federated services, and digital sovereignty isn't about idealism, it's a way to keep the internet free and to help reduce the already enormous political power of Big Tech.

Big Tech's Political Power

Big Tech - we already know them, the Googles, Metas, Amazons, Xs, Microsofts, etc. Of course there are thousands of companies that collect your data and might be even more evil than these well-known corporations, but the scale and amount of power that these few giants accumulated make them a much more significant threat to the freedom of the internet.

Back in 2023, Brazilian lawmakers were discussing a new law, the "Fake News Act". Under this law, amongst other measures, platforms would be responsible for moderating content and would have to take measures to remove misinformation. In response, Google launched a campaign against the bill by placing a statement on its homepage. You can't underestimate the power of a homepage banner on the most visited website in the country to influence public opinion. Especially a site like Google, where people go to for information and generally trust its results.

Another episode of Big Tech interfering in Brazilian politics was exposed by The Intercept, when a congressman proposed an amend to reduce the liability of Big Tech in protecting children and teens online. The file submitted by the congressman had metadata showing it was actually written by a Meta employee.

Either by shaping the reality people see daily on their feeds and search results, or by directly interfering in the political process, the amount of power our data has granted these corporations is immense.

What's Data Ownership?

While Data Ownership can have very different definitions depending on context, the one I'm using here is a shorthand for these 4 pillars:

- Collection Consent: You decide if, when, how, and what is collected.

- Usage Consent: You choose how, by whom and for what your data can be used.

- Portability: You can easily move your data between services if you so desire.

- Convenience: It should be convenient for a you to act on any of the above.

As you can see, it doesn't entail things like data security and proper PII4 handling, as that should be a given (if not by basic common sense, in some places by law, like the GDPR, LGPD, CCPA, etc).

The Pursuit

While in an ideal world, all online services would live by these principles and have users own their data, that's just not where society is right now. So, what can we do to mitigate the damages?

While organized political action is probably what would yield the best results, individually we can adjust our digital habits to reclaim as much ownership of our data as possible. These adjustments exist on a spectrum: some are small and barely affect our routines, while others require significant lifestyle changes that may not be feasible for everyone.

I currently see myself in the middle of that spectrum, slowly moving towards higher impact changes. It's an enjoyable process, but it's not without its challenges.

What Is to Be Done?

Choosing our battles is key. Let's be realistic you're probably not going to be able to live free of surveillance and data collection anytime soon. But, we can at least reduce the amount of data we give away and increase the amount of data we own. Shifting that balance just a little bit is already a win in my books.

Follow the Data Trail

The first step of solving any problem is understanding it throughly, so finding out where you've already left your data and what's still harvesting fresh data from you is a good place to start. Because I've been using the internet for almost as long as I can remember, doing that was a bit of a challenge. For a couple of weeks I kept adding anything that popped in my head to a note on my phone, but that wasn't getting me very far.

Then I had an idea:

The base of most services is Email. It is the core technology that most other things connect to. I could analyze data from my own emails and find out where else I had accounts. Some email services will allow you to download your mailbox data in .mbox format (like Gmail does), so I downloaded mine and coded this tool5 that analyzes that data and comes up with a list of all the companies that have ever emailed me. Running the tool on every email account I had through the years and combining everything got me a gigantic but comprehensive list.

Triage

With the list from from the previous step in hand, I went through each item to determine next steps. I've separated the actions into 4 categories:

- Delete - (Delete the account, via a web UI when possible, or through support email if necessary. Also means unsubscribing if you only receive emails, but don't have an actual account on the service.)

- Migrate - (Migrate to an alternative service that provides more data ownership. Eventually deleting the old account.)

- Modify - (Keep service, but update the privacy settings of the service to reduce the amount of data being collected and/or change the way I use it.)

- Do Nothing - (If I'm okay with the current level of data ownership I have, or if there's literally no way to improve it.)

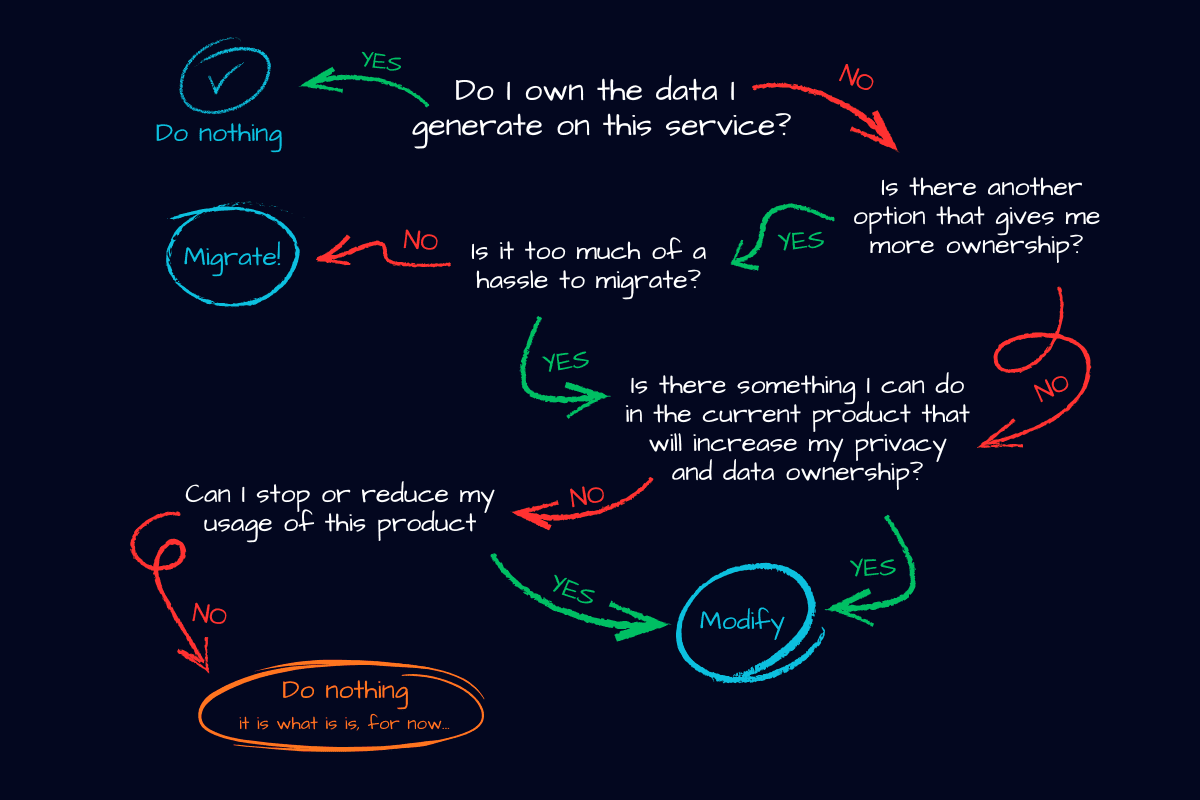

If the service/product was no longer in use, it would go automatically to the "Delete" category. If it was still in use, I'd follow the flowchart below to determine the next step.

This step took much longer than I expected, but gave me some great insight on my digital presence. After I was done with it, I had a list of actionable items to work on.

Taking Action

Now that I knew what to do it was time to start doing it... And I did.

In the past few months I've spent dozens of hours between sending emails to different companies, replacing apps I used with alternatives, and digging through config pages changing privacy settings. I'm not completely done yet, but I'm in a much better place compared to where I started, and that's the whole point. Each task I've checked off my list felt like getting slightly cleaner. You know that feeling of squeezing out a zit? Just like that.

Some companies are harder to deal with than others. Some have made me wait weeks for a response, some have been downright hostile. But being persistent, polite, and knowing your rights is key.

- Rely on the open source community. Most of the time there's a fully free and open source alternative to the proprietary service/software you're using.

- Know the privacy laws that apply to you. Citing the exact wording of the law will help making companies comply with your data deletion and data portability requests faster.

- Explore all the settings pages. Even when you can't get rid of a service, there's a lot you can improve by just changing a few settings.

- Choose your core tech wisely. If you're planning to make changes like your OS, browser, email provider or some other core technology that servers as a base for other services, get that done before you start with the smaller changes.

My Core Tech Choices

Though I'd very much like to list out all the services, apps and digital products I'm using, and why I picked each one, let's stick to the core tech for now. This is a very personal section, you might end up with different options based on your needs and preferences, but here's what I've chosen:

- Main Workstation OS: Migrated from MacOS to Ubuntu Though MacOS wasn't all that bad either. Out of all Big Tech, Apple is probably the one that values user privacy the most. I've ended up picking a Linux distro to be able to run it on non-Apple hardware.

- Mobile OS: I kept iOS here. There's not really a good alternative to it at this point. GrapheneOS and other ungoogled versions of Android are just not there yet, but I'm keeping a very close eye on their development.

- Browser: Migrated from Chrome to Helium. I've tried a lot of browsers in the past, but always ended up going back to Chrome for one reason or another. Helium is the one I've liked the most so far. It's a Chromium-based browser that looks and works very much like Chrome, but with a lot more privacy baked in. It is also fully open source and also doesn't try to push Web3 crypto bullshit on me.

- Email Provider + Cloud Storage + Calendar: Migrated from Gmail to Proton Mail. Like I said before, hosting your own email server is a pain, so I ended up with a provider that offers privacy and data ownership by design. The main difference here is that Proton is a paid service. That's because with Proton, the email service is the actual product they sell, while with free providers, the email service is just a way for them to get what trully is the product they're selling: your data. I've analyzed a lot of providers, and Proton is the one I thought offered the best balance between privacy and convenience. Price also isn't bad, especially if you get their bundle plan with other services to replace stuff you might be already paying for anyway. Considering I was already paying for cloud storage and a VPN, Getting Proton's bundle actually saved me money even thought I was paying for the email service.

- Social:

- Migrated from X to Bluesky. Bluesky is a federated social media network that is built on the idea of decentralized social media. Leaving X was a no-brainer, it's hard to justify being on a network owned by a nazi sympathizer and filled with bots, spam and well... nazis.

- WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram are a bit harder to leave for me. I do activelly use WhatsApp and Instagram every day, and keep Facebook around for its Marketplace and my work-related need for a Meta account. Though I haven't stopped using any of them, I've been reducing the amount of time I spent on these, and I've tinkered with the apps' privacy settings and my phone's own settings to reduce as much as possible the amount of data I'm giving away.

- Notes and Documentation: From Notion to AFFiNE. AFFiNE is really similar to Notion, but self-hosted and open source. It doesn't have the limitations of Notion's free account, and has a pretty cool edgeless/whiteboard mode.

What's Next?

I'll eventually finish working on my list, and will keep an eye on the developments of alternative tools to the ones I'm still using but are not offering me the level of data ownership I want. I might update this post as I go along, if something significant changes. Thanks for reading and for being interested in reclaiming your data ownership.

Footnotes

-

When companies (like airlines and apps like Uber) use all of the data they've gathered about you (and other users) to create custom pricing to each user, trying to approach the reservation price6. ↩

-

When recommendation systems (like those on YouTube or TikTok) nudge users toward increasingly extreme content to maximize engagement. Over time, this can shift public discourse and individual beliefs in harmful ways. ↩

-

The use of personal data to micro-target users and manipulate voter behavior. The Cambridge Analytica scandal is a prominent example. ↩

-

PII (Personally Identifiable Information), which is any data that can be used to identify a specific individual, either directly or indirectly. Stuff like full names, emails, IP addresses, etc. ↩

-

When I say I've coded this, what I really mean is that I coded a PoC, then got AI to build the whole UI around it. The tool currently only works for .mbox files, I know Outlook uses a different format, but I don't plan to support it at the moment. The tool is open source on GitHub, so feel free to contribute and maybe add that support if you feel so inclined. ↩

-

Reservation price is a limit on the price of something. It's the highest price that a buyer is willing to pay, and the lowest price a seller is willing to accept. ↩